to contact: tarlowart@gmail.com

"there is about him something of the storyteller, even if we never quite figure out what the story is. he makes us wonder what his people get up to when they aren't in the picture-and that is after all one of the perennial aims of painting." the late john russell in a new york times review of my '81 show at fischbach gallery

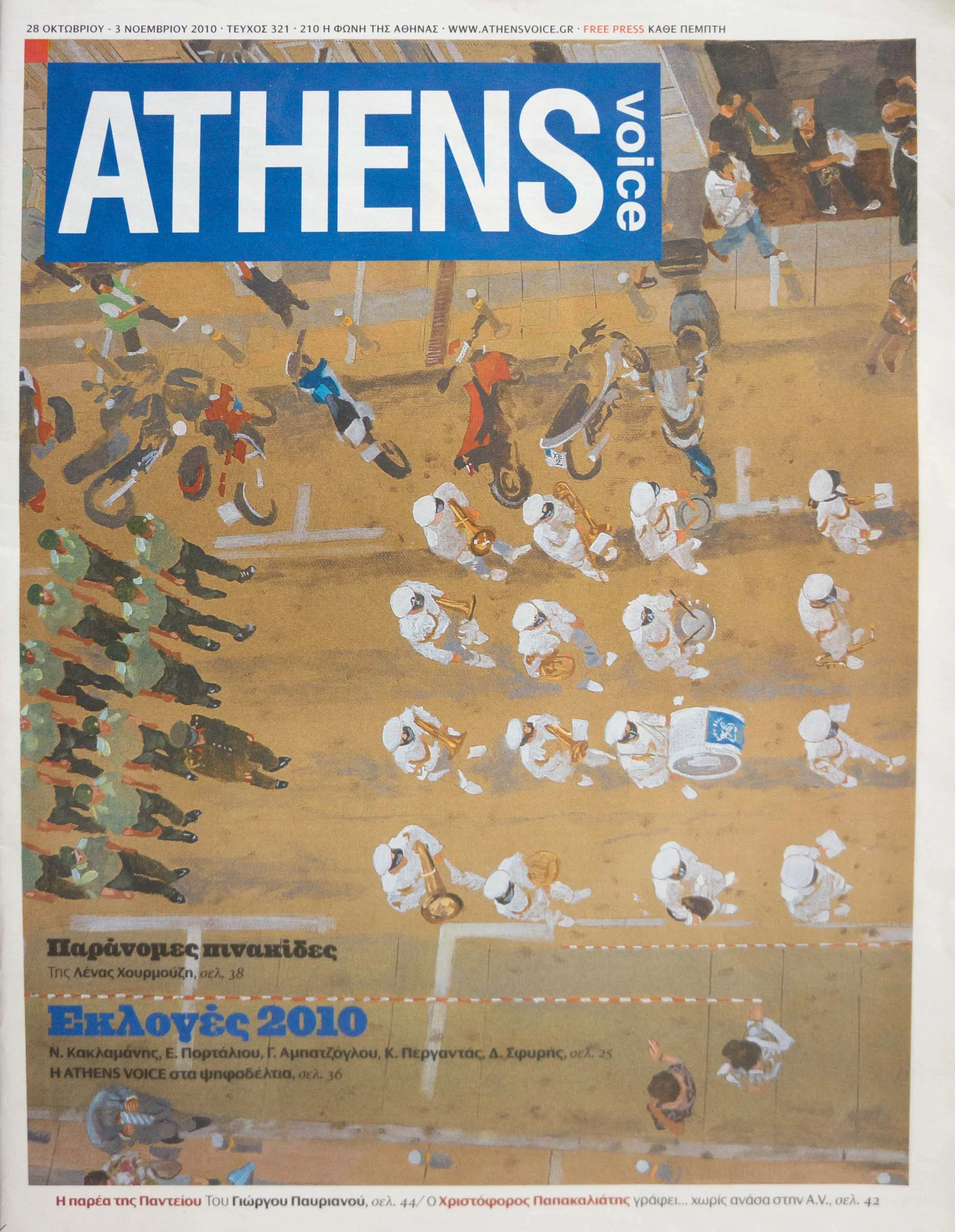

the cover of the athens voice, nov. 3, 2010. the painting on the cover is a detail of parade, which you can find under the drop down menu: greece/recent.

the occasion was my solo show at skoufa gallery in athens. the article title" athens from the heart."

an article was published feb. 1, 2014 in the melbourne, australia newspaper neos cosmos, written by helen velissaris.

http://neoskosmos.com/news/en/philip-tarlow-tsarouchis-american-protege

melbourne has the largest population of greeks in the world, outside of greece itself. go to:my story, below, for details about my life during the 15 years i lived and painted in greece. this article led to a phone meeting with the director of the hellenic museum in melbourne, which in turn has resulted in plans for an exhibition of the athens school painters yannis tsarouchis, yorgos manousakis, niki karagatsi and myself. dates for this show, which will travel to other cities in europe and the states, will be finalized soon.

SCROLL DOWN: for my complete, unedited answers to helen's excellent questions

1. Tell me about your first impressions of Greece? Did you feel like an outsider for long?

I read lots of Greek mythology as a kid, so for me Greece was a land of larger than life characters with larger than life stories. As it turned out, I was not far off the mark.

My very first impression of Greece took place on Kyrkyra, or Corfu. I was on a ferry from Yugoslavia, following a summer-long trip hitchhiking through Europe. I met British sculptor Henry Moore as I was getting off the boat, and he invited me to dinner at the resort he, his wife and daughter and gallery director were staying at. I agreed to join them. As we got off the boat, I was approached by a boy of about 8. He looked directly at me and said, in broken English "come home with me" (Ella spiti). That was my first contact with a Greek citizen.

I followed him and ended up staying at the small pension run by his family. After leaving Corfu, I took the ferry for Piraeus, then the subway to Athens. As we sailed through the Gulf or Corinth, I imagined ancient battles between Greeks and Persians and got my first whiff of the aromatic plants that grow on the mountainsides. I was beginning to fall in love with Greece.

In search of my friend Joe, with whom I had been hitchhiking, I took the ferry to Mykonos, where I met my future wife, Marina Karagatsi, who was sitting at a coffee shop with 3 friends. She gave me her number and when I returned to Athens we began dating. Before long, I had met her mother, the painter Niki Karagatsi.

So my first impressions of Greece were: the wild, intoxicating beauty of Mykonos, untouched as yet by tourism as it was in 1963; Omonia Square in Athens, where I slept on the roof of a third rate hotel to save money, and went to sleep each night under the starry sky with the honking of traffic below; and chic Kolonaki Square. Marina and Niki lived not far from the square, where I rented a small apartment and began getting to know her friends. One of them, Angelos Delivorrias, now curator of the Benaki Museum, warned me after a few months of speaking English in my presence, "you'd better start learning Greek right away, because we're getting tired of having to translate everything into English for you!"

Always a lover of languages, and with the advantage of a very good ear, I began, with Marina's help, to voraciously absorb everything I heard. If there was a word or phrase I didn't understand, I would always ask, and I had a notebook with me at all times, where I wrote new words I learned that day.

One day, a taxi driver was upset and yelled at me "vre vhodi!" I asked Marina what it meant and she responded "he's calling you a cow!" I though "is that a bad thing?" And so it went.

So from day one, I was totally immersed in a culture that seemed so exotic to me, in a good way and yet so inexplicably familiar. My first impression, I would say, was kind of like the feeling of extended family. When I walked down the street, if there were people I didn't know, they seemed more like people I hadn't yet met.

On November 22, 1963, Marina and I were at a party at the home of Angelos Delivorrias. Of course all were shocked to learn of the assassination of JFK. But I was a newcomer and as yet neither spoke nor understood Greek. While everyone was very understanding, it was the one moment when I felt completely isolated and alone. There was a kind of surreality at not being able to share my grief with fellow Americans and being at a party where everyone was having a great time and I could understand nothing.

TSAROUCHIS:

1. Many people know him through his art, but you knew him on a personal level.

What fascinated you about him?

tsarouchis in byzantine attire, 1989 just one day before his death at 79.

photo: yiorgos tourkovasilis

A few days before his death in 1989, Tsarouchis had his assistants and friends dress him in the magnificent attire of a Byzantine Archbishop, so that he would be ready to leave, like Kavafi’s “Kyr Manoueel, ton Komnino.”

This striking, some might say theatrical gesture on the part of Tsarouchis only days before his death says more than thousands of words could about who he was.

As soon as I laid eyes on him, I knew I was in the presence of a great artist and philosopher, whose magnitude was matched only by his humility.

I saw in his work the mastery of a Titian or Vermeer, but in the clothing of a Byzantine Emperor. The man knew what painting was, and, as he told me more than once, he knew it went far beyond “subject matter.” I loved that he remained a student his entire life, and took every opportunity to study the great masters. During the years of the junta, when he moved to Paris, you could find him in the Louvre with his drawing pad and colored pencils, sketching ancient greek mosaics or perhaps a 1st c. fayoum portrait. always the student. always learning. When i sent a book of his work to my old friend, the late Henry Geldzahler, then curator of the new 20th century art wing at New York's Metropolitan museum, he immediately wrote back, declaring Tsarouchis a "major 20th c. artist" and proposing a major show at P.S. 1. for more on this, go to my "story" page.

tsarouchis dances zeibekiko

I learned much by spending time in his studio, for which I continue to be deeply grateful. He had the capacity to continue painting while visitors, whether it was one or many, wandered about as the voice of his friend and collaborator Maria Callas could be heard.

His stated goal of marrying east and west was lofty, and it was one I believe he realized. I learned from him what exactly this meant, and began to recognize signs of each strand of the fabric that constituted east and west: in the art of the Byzantine era as well as in the art of the great practitioner of Greek shadow theatre, Sotiris Spatharis, whose “billboards” as you might call them, advertising his performances, with their Matisse-like broad areas of color were a profound influence on the early work of Tsarouchis.

The last time I saw him, before leaving Greece for the USA, it was as if he knew it was our last visit. He came to the gate surrounding his Marousi studio and, with his hands on the black metal bars, looked long and hard at me as I drove off.

What parts of his character did you or didn’t you like?

Was there a dark side to him?

This should be said with a Yiddish accent: So what’s not to like?

I knew that Tsarouchis’ humor and aphorisms, known throughout Athens, were on the one hand a large part of who he was. He was famous for “In Greece, you are whatever or whomever you declare yourself to be.”

On the other, they constituted a wall, protecting an extremely sensitive soul from the arrows and daggers of lesser beings. So while I thoroughly enjoyed his sometimes wicked humor, I always took it with a grain of salt.

I understood when I asked him to look at new paintings that to have critiqued them as a teacher was simply not who he was. So I didn’t take his silence personally. When he agreed to write a piece for the catalogue of my 1974 exhibition at Ora Gallery in Athens, something he rarely did, I took it as an affirmation that he did, indeed value my work. As I did when he asked to exchange one of his finer figure drawings for one of my watercolors.

I loved that he cared about his friends and cared about his country. I loved that he was like a wandering philosopher, and you could walk with him from Kolonaki to Syntagma, as I did many times, and discuss Ancient Chinese painting, the flaws and inconsistencies of the current government, Plato or Vermeer, all while walking through traffic and honking vehicles with extraordinary swiftness.

I loved that in 1977 he re-translated, designed sets and costumes and staged Euripides Trojan Women in a parking lot in the center of Athens, at a time when something like that was unheard of. And that, while driving him from Marousi to Athens and back one day, he spent the entire time reading his translation to me and asking for feedback. There was a lot to love.

2. What was so appealing about painting the everyday life of Greece?

I learned from my mother-in-law Niki that it was possible to do what I had always dreamed of doing: to make intimist paintings in the genre of Vuillard and Bonnard in a way that was contemporary and didn't feel like a throwback.

o teleftaios pastas 1969 watercolor

When I was in kindergarten, my teacher remarked, in an evaluation of me as a student, that I was fascinated by construction workers, which ended up being the core of my subject matter during my fifteen years in Greece. Niki didn't drive, so often she and I went together to little hat maker shops in Pireaus, to third rate Eastern European circuses that came to town, shoemakers and so on. My good friend, painter Yiorgos Manousakis and I once went to have what we called "o teleftaios pastas," or the last patsas served in the magnificent, vibrant & richly colorful outdoor market directly opposite the port of Piraeus, which was scheduled for demolition the next day. We both made paintings of the market that day, and mine hangs in our living room. patsas, by the way, is tripe soup.

In short, everyday life in Greece was such a rich experience for me as an American, and so many of my idols, like Vuillard and Bonnard had shown me the way, it was like a match made in heaven for Niki Kargatsi to become my mother-in-law. What I had experienced as great but somehow unreachable art, she turned into a simple drive down to Piraeus, where we could fully immerse ourselves in a still vibrant culture of tiny, family owned businesses with rich interiors, complete with fabulous mirrors and patterned wallpaper that were a painter's dream and characters who fit into that environment like a seamstress in a Vuillard family interior. I was in heaven.

3. Living in Plaka in the thick of things would have been impressive. Did you find a lot of your inspiration just in walking down the street?

The Tower of the Winds 2010 oil on linen

Actually, I didn't even have to walk down the street. Out my studio window, dead in front of me, was the Tower of the Winds, which became one of my main subjects during the years I spent in that studio. Of course it changed dramatically with the time of day, the weather and the seasons. So, like Monet with his haystacks, I painted the Tower in all conditions.

kolatsio egg tempera on board 12x24"

Just down the street, also facing the tower, a beautiful neoclassical structure was torn down during the Junta and in it's place a very ugly massive cement structure began to rise. The workers who were building it, on the other hand, seemed ideal subjects for portraits, with their makeshift hats made from newspaper and their weather worn faces often reminiscent of Byzantine icons. I began painting them individually and finally as a group, in a large horizontal frieze-like painting that was the centerpiece of one of my solo shows at Ora Gallery in the '70's.

To answer the question more directly, I wasn't drawn to paint the Plaka itself, as it had become too much of a tourist attraction had and lost it's vitality and character as a neighborhood.

4. Describe your impressions of the Junta:

One morning in April 1967, we woke up and turned on the radio only to hear military music and the National Anthem playing over and over. I was perplexed, but Marina and Niki immediately said "praxikopima," or "it's a military coup." As an American I was completely clueless, while they of course had lived through many similar moments. "Quick," they said, "go down to the bakery and the grocers and get as much bread, milk, etc. as you can." We already had a good supply of Andros olive oil, so that was taken care of.

I was shocked at the curfew, also a new experience for me, and the tanks surrounding Parliament, with their guns aimed at the crowds that had gathered in Syntagma Square. Next morning in Kolonaki square some artist friends had gathered and were already discussing an underground resistance. A few months later, I was shocked to learn of the disappearance of our pediatrician, who we learned had been imprisoned and tortured by the Junta because he had planted a few bombs. One day as I was waiting to cross the street, I overheard a conversation in hushed tones about how the Junta could be overthrown. When the light changed, two guys standing next to me began chasing them, and it suddenly dawned on me that there were spies, or "chafiedes" everywhere. It wasn't even safe to play Theodorakis, whose music had been banned, in the privacy of your own home!

Marina and I ventured down to the Polytechneio in '74, the day of the terrible events that took place there. As we approached, students being chased by the police came running towards us and we heard gunfire. We too began running, and I remember hearing the zing of bullets. Much later that night, Voula, the live-in maid we had, who was just a girl, came back to the apartment, shoes in hand and stockings shredded from running, ghostly pale and obviously shaken. She had been caught up in the turmoil and locked inside the Polytechneio along with the students. She was able to get out and flee to safety only when the tanks arrived and broke down the locked entry gates. Her descriptions of students being beaten and shot remain vivid in my memory.

Another incident I recall is tragic-comic. My friends: the painter Manousakis, the cinematographer Pandelis Voulgaris and I decided to attend a massive rally organized by Papadopoulos at the Stadium. We impersonated journalists with fake passes we had made, and intended to document the Fellini-esque event with our video cameras. The Junta's intent was to portray the illustrious history of Greece, going back to ancient times and leading to the present and the crowning glory of the Junta. We were in the center of it all as the pagent began. Planes flew low overhead dropping pro-Junta pamphlets, ancient chariots came roaring by and then, suddenly, the dictators themselves appeared: Papadopoulos, Pattakos, et al. In full military garb, they marched towards us. We were so caught up in filming them, stepping backward as they approached, that they almost trampled us before we realized we had to move fast. We turned and ran like hell. Later that evening we had a good laugh. Both Pandelis and Manousakis created very effective short videos, distributed underground, mocking the Junta.

When I learned of the American involvement in the coup, and that Papdopoulos had actually been trained in the U.S., I felt deep shame for my country. I would say the Junta precipitated a loss of innocence on my part, and an awakening to the pain of people all over the world who continue to live under brutal dictatorships.

5. How would you describe the Greek psyche?

It’s a difficult question, since it would be presumptuous of me as an American to describe the Greek Psyche.

o kyrios yiannis oil on linen 20x12.5"

That said, I would say that the Greek psyche is certainly colored by it’s recent and distant past. The larger than life characters that populate ancient Greek mythology, with their all too human qualities of passionate, sometimes impulsive actions, jealousy, revenge, heroism, a feel for the sublimely ridiculous, artistic gifts and often brilliant solutions to problems, I believe are alive and well in the Modern Greek psyche. As well, the lessons learned from 400 years of Turkish occupation can be seen the the daily life of the contemporary Greek citizen: mistrust of authority, back door solutions to problems, etc. I believe these learned reactions and behaviors are fast fading with a new generation for whom the experience of being occupied and dominated is fading quickly, or not even an issue.

I was struck, in my first contact with Greeks, by their unusually high level of artistic abilities, which I think manifest in all the arts. Of course, as an American, I was also struck by the closeness and intimacy of family life which was even more intact back when I first arrived, in the ’60’s. When I introduced the concept of a baby sitter for our son Dimitri, my mother-in-law Niki thought I had said baby sister, a phrase she continued to use even though she knew it was incorrect. Why would you want to have someone who is not family looking after your child? That says it all.

As an American I was privileged to have unwittingly dropped into a very vibrant artistic milieux. That, plus my rapid command of the subtleties of the language, allowed me glimpses into many extraordinary aspects of the Greek psyche, especially as it expressed artistically. For example, Koun’s production of Aristophanes The Birds, with music by Hadzidakis and costumes by Tsarouchis, was a masterpiece which traveled to the World Theatre Festival in London. The Athens production was so charged with the genius of Aristophanes and so alive as a production, you actually felt the presence of the great playwright in the theatre. His sexuality was in your face, with no holds barred. His humor: ribald, daring, intelligent permeated the space. This was only one example of the very particular brilliance of the Greek psyche.

sotiris spatharis in his plaka workshop, 1971 photo:p. tarlow

Another example I would give is the great practitioner of shadow theatre Sotiris Spatharis, who I was privileged to have known. His being expressed core elements of the Greek psyche: he turned tragedy and hardship into humor in a way that was artistically brilliant and inimitably Greek. Karaghiozis was the Greek everyman: sly, ridiculous, clever, lovable and at the same time completely and disarmingly innocent. He was poor. So poor that, when it rained, he went outdoors, to escape the many leaks in his roof. He lived by his wits, which he repeatedly and hilariously used to outsmart the Turkish oppressors.

6. I’ve always found it difficult to start an article and I’m sure it must be difficult for you to start a painting. How do you go about putting the image in your head onto canvas?

Actually not. But I would qualify that. There are three distinct kinds of work I currently do. One is very realist and is exemplified by the recent paintings I’ve shown at Skoufa Gallery in Athens, as well as the ones I created during my fifteen years living in Greece. You can see these on my website, under “Greek Period” on the menu bar:

The other is exemplified my my current abstracted landscapes, which I show at Gremillion & Co. Fine Art in Houston, Texas. This work can be seen by clicking on the rest of the items on the menu bar. The progress of this new work can be followed on my blog page, which is updated almost daily, unless we’re traveling, and tracks the progress of new work from inception to completion: http://philiptarlow.com/updatesnews/

And the third are the plein air paintings I make at a local creek, weather permitting, upon which the abstracted landscapes are all based.

The realist work is created very differently than the abstract and plein air paintings. It is almost all based upon photos I’ve taken on site, which are then enlarged, traced and transferred to the painting surface. The painting really begins when I select the photo or photos to use. Once the traced drawing is transferred to the painting surface, which is a tinted ground, usually a tan-ish color, which I learned from Tsarouchis and is based upon Byzantine prototypes, the actual painting begins. The first brush strokes on that surface, with it’s white drawing (I use white transfer paper) are actually very easy.

example of an "unfinished" painting of the acropolis with figures. in retrospect, i wish i had left it in this mysterious, surreal state.

Since I know pretty much where the painting is headed, watching it manifest in color is extremely pleasurable, and I feel more like a vehicle for creation than the creator. The difficulty you speak of arises when I reach a certain point in the painting where I could stop, even though logically the painting is “unfinished.” When I first worked up the courage to actually stop with over half the painting “incomplete” or “blank,” and it was shown along with the rest of the “completed” paintings at Skoufa, it was the first to sell! That acknowledgement by the public that my new understanding of what is a “completed” painting forever changed my way of working. And it affirmed my belief in what Tsarouchis once suggested to me, that all good or great painting is “abstract.”

The plein air paintings are all executed in one sitting, usually an hour or less, in oil on a 16x16” (41x41cm.) canvas. The setting: very remote and wild, with the creek, rushing over the rocks and swollen with snowmelt in the spring, more gentle and peppered with fallen orange-yellow-red leaves in the fall, instantly puts me into a state I can only describe as ecstatic. Once I set up my portable easel and squeeze the colors onto my palette, my logical mind takes a walk and I work quickly and with certaintly, rarely second guessing myself. Once again, the difficulty I encounter is when to stop. If I get too descriptive and my reasoning minds begins creeping back in, I’m in trouble. It’s kind of like cooking: you know when the dish is complete, and anything you add will only detract from the perfection of the dish. But sometimes you do it anyway, and usually the dish sucks.

My abstract biomorphic paintings are a bit like the plein air paintings. They are very easy to begin, usually on a horizontal surface like a table. Gestural marks are made, sometimes loosely based upon the plein air paintings hanging on my studio wall. Sometimes I’ll take a painting I think may be complete to our house, about 500 feet from my studio. Mikela and I live with it for a day or two, at which point it becomes clear whether or not it needs more work.

I document my process as much as possible with photos and video, which allows me to know better where I've been and where I might be headed.

Once again, the difficulty is in knowing when to stop, not in starting the piece. So as I write this I realize that challenge runs through all of the three ways I work.